For Clients & Friends of The Gualco Group, Inc.

IN THIS ISSUE – “We Can’t Keep Going Like This”

POLITICS

- Uh-Oh…Newsom’s Voter Rating Slips; Recall Margin Narrows

- 2022 Ballot Measures Certified (What Recall?)

- State Treasurer’s Executive Files Sexual Harassment Charge

LEADING INDICATORS & CRITICAL ISSUES

- Californians’ Income Jumped in July; Other Key Economic Data Upbeat

- Newsom Signs $6-Billion Broadband Deployment

- Drought, Fires, No Insurance Push Iconic California Industry to the Limit: Winegrape Growers “Can’t Keep Going Like This”

- Health Care Expansion Eludes Governor & Legislature

- Wealthy Activists Reshaping Criminal Justice; Stay Below Radar

Capital News & Notes (CN&N) harvests California policy, legislative and regulatory insights from dozens of media and official sources for the past week. Please feel free to forward this unique service.

READ ALL ABOUT IT!!

FOR THE WEEK ENDING JULY 23, 2021

Uh-Oh…Newsom’s Voter Rating Slips; Recall Margin Narrows

KRON-TV & CalMatters

Gov. Gavin Newsom’s approval rating has slipped to 49%, according to an Inside California Politics/Emerson College poll released Thursday.

That’s a dip from the 54% and 52% ratings he garnered in May polls from the Public Policy Institute of California and UC Berkeley’s Institute of Governmental Studies, respectively.

The new poll found that 48% of voters would keep Newsom in office in the Sept. 14 recall election, compared to 43% who would recall him and 9% who remain undecided.

But — in a sign that Newsom will face political challenges even if he survives the recall — only 42% of voters said they would re-elect him in 2022, compared to 58% who said they think it’s time for someone new.

In another series of warning signs, voters mostly gave Newsom “poor” marks for his response to the pandemic, homelessness, wildfires and drought.

Of the 46 candidates running to replace Newsom, Larry Elder received the most support, with 16% of poll respondents saying they would vote for him. Kevin Faulconer and John Cox were tied at 6%, while Kevin Kiley and Caitlyn Jenner were tied at 4%.

A majority of voters — 53% — remained undecided.

On Saturday, the California Republican Party executive committee is to decide whether to move forward with an endorsement process — a debate that has already set off fierce intraparty fighting.

2022 Ballot Measures Certified (What Recall?)

CalMatters & Secretary of State

California voters will decide the fate of single-use plastic packaging in November 2022, thanks to a measure that qualified for the ballot late Monday. The measure would levy a one-cent tax on plastics manufacturers for each single-use packaging, container or utensil they sell in California; require them to sell 25% fewer of those products; and ensure that what they do sell is reusable, recyclable or compostable by 2030. It would also ban food vendors from using Styrofoam containers. The measure, which is estimated to bring in a few billion dollars of tax revenue annually, goes further than two similar proposals that died in the state Legislature in 2019 and 2020 amid fierce opposition from powerful industry groups.

Assemblymember Lorena Gonzalez, a San Diego Democrat who authored the 2020 bill, during a floor debate last year: “I want to remind folks that we can act or we can wait for a proposition to be put on the ballot and pass, because it will pass. We can have a hand in what this looks like or we can allow other people to do it for us.”

Other measures that have qualified for the November 2022 ballot: a referendum to overturn California’s flavored tobacco ban, a measure to legalize sports gambling, and a measure to undo a state law limiting damages in medical malpractice lawsuits.

https://www.sos.ca.gov/elections/ballot-measures/qualified-ballot-measures

State Treasurer’s Executive Files Sexual Harassment Charge

Sacramento Bee

A former state employee is suing California Treasurer Fiona Ma alleging sexual harassment, wrongful termination and racial discrimination, according to a complaint filed last week in Sacramento Superior Court.

The lawsuit alleges Ma exposed her backside to Judith Blackwell, then the executive director of the California Tax Credit Allocation Committee, while the two shared a hotel room. The action made Blackwell “uncomfortable,” according to the lawsuit, which says Blackwell was “fearful to comment on Ms. Ma’s lewd behavior.”

The complaint also says Ma gave Blackwell jewelry, paintings and edible marijuana as gifts, and that the women would go out to dinner together frequently, along with Ma’s chief of staff.

In an email to The Bee, Ma denied Blackwell’s allegations.

“I am saddened and disappointed by these baseless claims,” Ma wrote. “I want to thank everyone for the outpouring of support I’ve received today. To set the record straight, we have repeatedly refused to respond to the attorney’s attempts to settle. We look forward to bringing the truth to light in court.”

In May 2020, the complaint says Blackwell stayed with Ma at an Airbnb rental where Ma climbed into Blackwell’s bed while she was trying to sleep. Blackwell pretended to be asleep “out of fear and confusion,” it says.

Blackwell began working for Ma in September 2019 overseeing the state’s housing tax credit program. She also oversaw the California Debt Limit Allocation Committee, a separate program in the Treasurer’s office after Ma fired the director of that program, according to the complaint.

In September, Blackwell had a stroke that kept her from working for two months. When she returned, she says Ma assigned her enough work for two people and required her to work into the night, according to the complaint.

In January, Blackwell was fired, her lawyer Waukeen McCoy said.

Blackwell, who is African American, believes she was replaced by a “less-qualified Caucasian female,” according to the complaint.

https://www.sacbee.com/news/politics-government/capitol-alert/article252888703.html#storylink=cpy

Californians’ Income Jumped in July; Other Key Economic Data Upbeat

State Dept. of Finance

Driven by transfer payments, California’s personal income increased by 42.8 percent on a seasonally adjusted annualized rate (SAAR) in the first quarter of 2021, marking the largest personal income growth since a 29.7-percent increase in the first quarter of 1950. U.S. personal income increased by a record 59.7 percent in the first quarter of 2021. California’s share of U.S. personal income was 14.2 percent, down from 14.6 percent in the fourth quarter of 2020, and in line with the 2019 average of 14.2 percent.

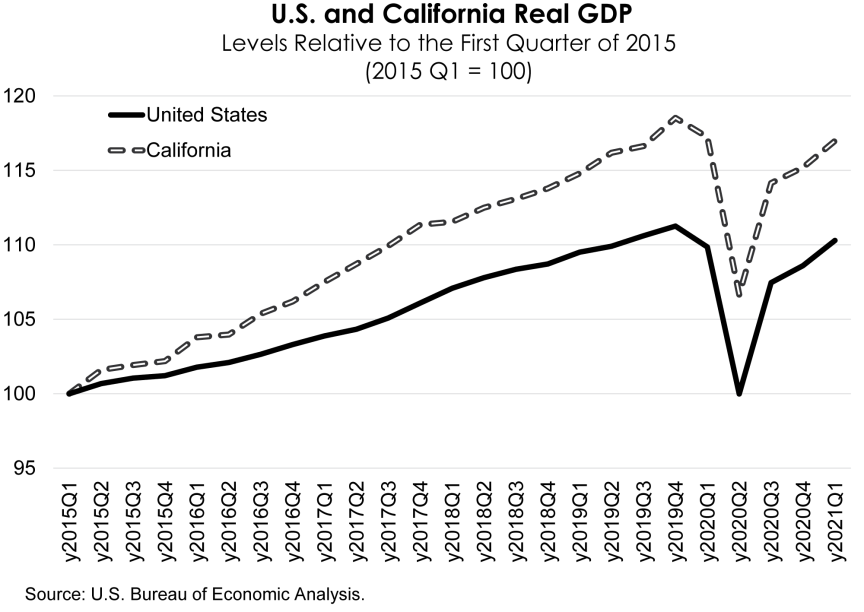

California real GDP grew by 6.3 percent (SAAR) in the first quarter of 2021, following 3.8-percent growth in the fourth quarter of 2020. U.S. real GDP grew at 6.4 percent in the first quarter of 2021 after growing 4.3 percent in the fourth quarter of 2020. As of the first quarter of 2021, California and U.S. real GDP were near their third quarter of 2019 levels, and 1.3 percent and 0.9 percent (respectively), below their fourth quarter of 2019 levels. California’s share of U.S. real GDP was unchanged at 14.7 percent for the third consecutive quarter, in line with the 2019 annual average of 14.7 percent.

LABOR MARKET CONDITIONS

nThe official U.S. unemployment rate rose 0.1 percentage point to 5.9 percent in June 2021. Civilian unemployment increased by 168,000 as civilian employment fell by 18,000 (the first decrease since falling by 25 million in March and April 2020) and the labor force increased by 151,000 persons. There were 7.1 million fewer employed and 3.4 million fewer persons in the labor force in June 2021 than in February 2020. The U.S. added 850,000 total nonfarm jobs in June 2021, the largest increase since gaining 1.6 million jobs in August 2020. Nine out of the eleven major industry sectors gained jobs: leisure and hospitality (343,000), government (188,000), trade, transportation and utilities (99,000), professional and business services (72,000), education and health services (59,000), other services (56,000), manufacturing (15,000), information (14,000), and mining and logging (12,000). Construction (-7,000) and financial activities (-1,000) lost jobs. As of June 2021, the U.S. has recovered 69.8 percent of the 22.4 million jobs lost in March and April 2020.

California unemployment rate remained unchanged at May’s revised rate of 7.7 percent in June 2021. California labor force increased by 36,000 in June 2021 with 25,000 more employed and 11,000 more unemployed. There were 1.1 million fewer employed and 534,000 fewer people in the labor force in June 2021 than in February 2020. After adding 73,500 nonfarm jobs in June 2021, California has now recovered 54.2 percent of the 2.7 million jobs lost in March and April 2020. Eight sectors added jobs: leisure and hospitality (44,400), government (7,400), other services (7,200), educational and health services (6,000), trade, transportation, and utilities (5,300), manufacturing (4,200), professional and business services (3,400), and information (500). Construction (-3,000), financial activities (-1,700), and mining and logging (-200) lost jobs.

BUILDING ACTIVITY & REAL ESTATE

nCalifornia permitted 113,000 housing units (52,000 multi-family units and 68,000 single-family units) on a seasonally adjusted annualized rate in May 2021. This was down from 128,000 units in April 2021, but above the 77,000 units permitted in May 2020. From January to May 2021, permits averaged 126,000 units compared to 98,000 units in the same period in 2020 and 107,000 units in the same period in 2019.

July 2021

MONTHLY CASH REPORT

Preliminary General Fund agency cash receipts for the entire 2020-21 fiscal year were $4.783 billion above the 2021-22 Budget Act forecast of $201.775 billion. Cash receipts for the month of June were $4.74 billion above the 2021-22 Budget Act forecast of $23.109 billion.

nPersonal income tax cash receipts to the General Fund for the entire 2020-21 fiscal year were

$1.783 billion above forecast. Cash receipts for June were also $1.783 billion above the month’s forecast of $15.312 billion. Withholding receipts were $1.873 billion above the forecast of $5.072 billion. Other cash receipts were $782 million above the forecast of $11.067 billion. Refunds issued in June were

$854 million above the expected $537 million. Proposition 63 requires that 1.76 percent of total monthly personal income tax collections be transferred to the Mental Health Services Fund (MHSF). The amount transferred to the MHSF in June was $32 million higher than the forecast of $275 million.

Sales and use tax cash receipts for the entire 2020-21 fiscal year were $626 million above forecast. Cash receipts for June were $451 million above the month’s forecast of $2.766 billion. June cash includes the second prepayment for second quarter taxable sales.

Corporation tax cash receipts for the entire 2020-21 fiscal year were $1.31 billion above forecast. Cash receipts for June were $1.283 billion above the month’s forecast of $4.287 billion. Estimated payments were $1.285 billion above the forecast of $3.975 billion, and other payments were $4 million above the $387 million forecast. Total refunds for the month were $6 million higher than the forecast of $74 million.

https://dof.ca.gov/Forecasting/Economics/Economic_and_Revenue_Updates/documents/2021/Jul-21.pdf

Newsom Signs $6-Billion Broadband Deployment

Sacramento Bee

Gov. Gavin Newsom signed a bill this week to spend $6 billion over the next three years expanding broadband access throughout the state, prioritizing unserved, underserved and rural communities.

Much of the money will fund increased connectivity for rural communities with little to no network access and public spaces like schools and libraries with less access to high-bandwidth internet.

Newsom signed the broadband bill into law surrounded by students at Traver Joint Elementary School in Tulare County.

“The issue of access and equity — those are the two words that bring us here today,” Newsom said. “The spirit is that next generation that will be the beneficiaries of this historic, landmark investment.”

The bill passed with bipartisan support in the Assembly and Senate, with many legislators emphasizing how COVID-19 lockdowns revealed vast disparities in internet access throughout the state.

“This pandemic has shown that the digital divide is one of the most pressing civil rights issues of the 21st century,” said Assembly member Al Murasutchi, D-Torrance, in the Assembly floor session. “If you don’t have affordable, reliable internet access, you can’t get into the classroom. If you don’t have reliable internet service, you can’t telecommute and get into the workplace. For those who don’t have internet service, they can’t see their healthcare providers.”

The law establishes a deputy director of broadband, broadband advisory council and office of broadband and digital literacy at the California Department of Technology. The deputy director for broadband will be appointed by the governor and act as the point of contact for Caltrans, the Legislature, the commission and the third-party administrator.

More half of the money, $3.25 billion, is intended go toward increasing middle-mile infrastructure, which links major internet providers to a local access point like schools and hospitals. Building this middle mile will bring internet services to rural areas and create competition in urban communities that will lower prices.

The middle-mile construction will prioritize areas without sufficient high-bandwidth connectivity, such as elementary and secondary schools, higher education, healthcare institutions, libraries and tribal lands.

In fall 2020, more than a quarter of K-12 students and nearly 40% of low-income students did not have reliable internet access, according to data from the Public Policy Institute of California.

Another $2 billion will be used for last-mile projects to connect underserved households to high-speed internet. At least $1 billion of this allocation must be spent in rural counties.

Rural areas in California have the lowest access to broadband, as shown by the 2019 American Community Survey, with the exception of rural wealthy regions in Sonoma and Marin counties.

Although the bill passed unanimously, Assembly legislators brought up several concerns such as continued funding for operation and maintenance.

“Every year wildfires burn miles and miles of fiber optic cable … that have to be replaced at significant expense,” said Assemblyman Jordan Cunningham, R-San Luis Obispo, who nonetheless requested support for the bill as an important first step. “I don’t know if this bill really fully contemplates the operation maintenance costs.”

The final $750 million in the $6 billion allocation is slated to go toward a reserve to cover loan losses for local governments and nonprofits as they fund broadband projects.

https://www.sacbee.com/news/politics-government/capitol-alert/article252818568.html#storylink=cpy

Drought, Fires, No Insurance Push Iconic California Industry to the Limit;

Winegrape Growers “Can’t Keep Going Like This”

NY Times

- HELENA, Calif. — Last September, a wildfire tore through one of Dario Sattui’s Napa Valley wineries, destroying millions of dollars in property and equipment, along with 9,000 cases of wine.

November brought a second disaster: Mr. Sattui realized the precious crop of cabernet grapes that survived the fire had been ruined by the smoke. There would be no 2020 vintage.

A freakishly dry winter led to a third calamity: By spring, the reservoir at another of Mr. Sattui’s vineyards was all but empty, meaning little water to irrigate the new crop.

Finally, in March, came a fourth blow: Mr. Sattui’s insurers said they would no longer cover the winery that had burned down. Neither would any other company. In the patois of insurance, the winery will go bare into this year’s burning season, which experts predict to be especially fierce.

“We got hit every which way we could,” Mr. Sattui said. “We can’t keep going like this.”

In Napa Valley, the lush heartland of America’s high-end wine industry, climate change is spelling calamity. Not outwardly: On the main road running through the small town of St. Helena, tourists still stream into wineries with exquisitely appointed tasting rooms. At the Goose & Gander, where the lamb chops are $63, the line for a table still tumbles out onto the sidewalk.

But drive off the main road, and the vineyards that made this valley famous — where the mix of soil, temperature patterns and rainfall used to be just right — are now surrounded by burned-out landscapes, dwindling water supplies and increasingly nervous winemakers, bracing for things to get worse.

Desperation has pushed some growers to spray sunscreen on grapes, to try to prevent roasting, while others are irrigating with treated wastewater from toilets and sinks because reservoirs are dry.

Their fate matters even for those who can’t tell a merlot from a malbec. Napa boasts some of the country’s most expensive farmland, selling for as much as $1 million per acre; a ton of grapes fetches two to four times as much as anywhere else in California. If there is any nook of American agriculture with both the means and incentive to outwit climate change, it is here.

But so far, the experience of winemakers here demonstrates the limits of adapting to a warming planet.

If the heat and drought trends worsen, “we’re probably out of business,” said Cyril Chappellet, president of Chappellet Winery, which has been operating for more than half a century. “All of us are out business.”

Stu Smith’s winery is at the end of a two-lane road that winds up the side of Spring Mountain, west of St. Helena. The drive requires some concentration: The 2020 Glass Fire incinerated the wooden posts that held up the guardrails, which now lie like discarded ribbons at the edge of the cliff.

In 1971, after graduating from the University of California at Berkeley, Mr. Smith bought 165 acres of land here. He named his winery Smith-Madrone, after the orange-red hardwoods with waxy leaves that surround the vineyards he planted. For almost three decades, those vineyards — 14 acres of cabernet, seven acres each of chardonnay and riesling, plus a smattering of cabernet franc, merlot and petit verdot — were untouched by wildfires.

Then, in 2008, smoke from nearby fires reached his grapes for the first time. The harvest went on as usual. Months later, after the wine had aged but before it was bottled, Mr. Smith’s brother, Charlie, noticed something was wrong. “He said, ‘I just don’t like the way the reds are tasting,’” Stu Smith said.

At first, Mr. Smith resisted the idea anything was amiss, but eventually brought the wine to a laboratory in Sonoma County, which determined that smoke had penetrated the skin of the grapes to affect the taste.

What winemakers came to call “smoke taint” now menaces Napa’s wine industry.

“The problem with the fires is that it doesn’t have be anywhere near us,” Mr. Smith said. Smoke from distant fires can waft long distances, and there is no way a grower can prevent it.

Smoke is a threat primarily to reds, whose skins provide the wine’s color. (The skins of white grapes, by contrast, are discarded, and with them the smoke residue.) Reds must also stay on the vine longer, often into October, leaving them more exposed to fires that usually peak in early fall.

Vintners could switch from red grapes to white but that solution collides with the demands of the market. White grapes from Napa typically sell for around $2,750 per ton, on average. Reds, by contrast, fetch an average of about $5,000 per ton in the valley, and more for cabernet sauvignon. In Napa, there is a saying: cabernet is king.

The damage in 2008 turned out to be a precursor of far worse to come. Haze from the Glass Fire filled the valley; so many wine growers sought to test their grapes for smoke taint that the turnaround time at the nearest laboratory, once three days, became two months.

The losses have been stunning. In 2019, growers in the county sold $829 million worth of red grapes. In 2020, that figure plummeted to $384 million.

Among the casualties were Mr. Smith, whose entire crop was affected. Now, the most visible legacy of the fire is the trees: The flames scorched not just the madrones that gave Mr. Smith’s winery its name, but also the Douglas firs, the tan oaks and the bay trees.

Trees burned by wildfires don’t die immediately; some linger for years. One afternoon in June, Mr. Smith surveyed the damage to his forest, stopping at a madrone he especially liked but whose odds weren’t good. “It’s dead,” Mr. Smith said. “It just doesn’t know it yet.”

Across the valley, Aaron Whitlatch, the head of winemaking at Green & Red Vineyards, climbed into a dust-colored jeep for a trip up the mountain to demonstrate what heat does to grapes.

After navigating steep switchbacks, Mr. Whitlatch reached a row of vines growing petite sirah grapes that were coated with a thin layer of white.

The week before, temperatures had topped 100 degrees and staff sprayed the vines with sunscreen.

“Keeps them from burning,” Mr. Whitlatch said.

The strategy hadn’t worked perfectly. He pointed to a bunch of grapes at the very top of the peak exposed to sun during the hottest hours of the day. Some of the fruit had turned black and shrunken — becoming, effectively, absurdly high-cost raisins.

“The temperature of this cluster probably reached 120,” Mr. Whitlatch said. “We got torched.”

As the days get hotter and the sun more dangerous in Napa, wine growers are trying to adjust. A more expensive option than sunscreen is to cover the vines with shade cloth, Mr. Whitlatch said. Another tactic, even more costly, is to replant rows of vines so they’re parallel to the sun in the warmest part of the day, catching less of its heat.

At 43, Mr. Whitlatch is a veteran of the wine fires. In 2017, he was an assistant winemaker at Mayacamas Vineyards, another Napa winery, when it was burned by a series of wildfires. This is his first season at Green & Red, which lost its entire crop of reds to smoke from the Glass Fire.

After that fire, the winery’s insurer wrote to the owners, Raymond Hannigan and Tobin Heminway, listing the changes needed to reduce its fire risk, including updating circuit breaker panels and adding fire extinguishers. “We spent thousands and thousands of dollars upgrading the property,” Mr. Hannigan said.

A month later, Philadelphia Insurance Companies sent the couple another letter, canceling their insurance anyway. The explanation was brief: “Ineligible risk — wildfire exposure does not meet current underwriting guidelines.” The company did not respond to a request for comment.

Ms. Heminway and Mr. Hannigan have been unable to find coverage from any other carrier. The California legislature is considering a bill that would allow wineries to get insurance through a state-run high-risk pool.

But even if that passes, Mr. Hannigan said, “it’s not going to help us during this harvest season.”

Just south of Green & Red, Mr. Chappellet stood amid the bustle of wine being bottled and trucks unloading. Chappellet Winery is the picture of commercial-scale efficiency, producing some 70,000 cases of wine a year. The main building, which his parents built after buying the property in 1967, resembles a cathedral: gargantuan wooden beams soar upward, sheltering row after row of oak barrels aging a fortune’s worth of cabernet.

After the Glass Fire, Mr. Chappellet is one of the lucky ones — he still has insurance. It just costs five times as much as it did last year.

His winery now pays more than $1 million a year, up from $200,000 before the fire. At the same time, his insurers cut by half the amount of coverage they were willing to provide.

“It’s insane,” Mr. Chappellet said. “It’s not something that we can withstand for the long term.”

There are other problems. Mr. Chappellet pointed to his vineyards, where workers were cutting grapes from the vines — not because they were ready to harvest, but because there wasn’t enough water to keep them growing. He estimated it would reduce his crop this year by a third

“We don’t have the luxury of giving them the normal amount that it would take them to be really healthy,” Mr. Chappellet said.

To demonstrate why, he drove up a dirt road, stopping at what used to be the pair of reservoirs that fed his vineyards. The first was one-third-full; the other, just above it, had become a barren pit. A pipe that once pumped out water instead lay on the dusty lake bed.

“This is the disaster,” Mr. Chappellet said.

When spring came this year, and the reservoir on Dario Sattui’s vineyard was empty, his colleague Tom Davies, president of V. Sattui Winery, crafted a backup plan. Mr. Davies found Joe Brown.

Eight times a day, Mr. Brown pulls into a loading dock at the Napa Sanitation District’s facility, fills a tanker truck with 3,500 gallons of treated wastewater and drives 10 miles to the vineyard, then turns around and does it again.

The water, which comes from household toilets and drains and is sifted, filtered and disinfected, is a bargain, at $6.76 a truckload. The problem is transportation: Each load costs Mr. Davies about $140, which he guesses will add $60,000 or more to the cost of running the vineyard this season.

And that’s assuming Napa officials keep selling wastewater, which in theory could be made potable. As the drought worsens, the city may decide its residents need it more. “We’re nervous that at some point, Napa sanitation says no more water,” Mr. Davies said.

After driving past the empty reservoir, Mr. Davies stopped at a hilltop overlooking the vineyard.

If Napa can go another year or two without major wildfires, Mr. Davies thinks insurers will return. Harder to solve are the smoke taint and water shortages.

“It’s still kind of early on to talk about the demise of our industry,” Mr. Davies said, looking out across the valley. “But it’s certainly a concern.”

Health Care Expansion Eludes Governor & Legislature

CalMatters

Early in his term, Gov. Gavin Newsom positioned himself as the governor who would champion health care. He vowed to target rising prescription drug costs and find a way for the state to pay for care for all Californians, a key campaign promise. He also set a goal of creating a blueprint to better serve the Golden State’s growing population of seniors.

But two and a half years after taking office and still struggling to control a pandemic, the governor has had to focus much of his attention on COVID-19, so timelines for other health efforts have been pushed back.

Two of Newsom’s boldest health care promises — affordable medications and universal, state-funded health care — have made little progress during his term. And a third — a master plan for seniors — has been drafted yet actions will be phased in over the next 10 years. So enacting each of them in some form will likely come after Newsom’s term ends — even if he isn’t recalled in September.

Health advocates and experts praise the efforts, but some are less convinced that Newsom can deliver on mammoth goals like creating a state-funded, single-payer health system.

“It’s important not to lose sight of some historic steps taken in expanding coverage,” said Thad Kousser, a political science professor at UC San Diego. “But to be clear he campaigned on a single-payer pledge that a lot of people didn’t think was realistic, and I think the last few years have shown us that it will be incredibly hard to achieve.”

Even before the pandemic, the governor acknowledged that full-fledged plans for reforming health care would take years.

His team says the work is ongoing, pointing to the billions of dollars in this year’s budget to expand health coverage and services. “Governor Newsom is working in partnership with the Legislature to make health care more affordable and accessible for all Californians — regardless of their age, immigration status, or income,” a spokesperson for the governor’s office told CalMatters in an email.

Newsom has often claimed California is leading the fight against prescription drug prices.

But drug prices are still rising. Last year, drug manufacturers reported price increases of more than 16% on more than 1,200 prescription drugs to state regulators.

About three in 10 adults reported not taking their medications as prescribed at some point in the past year because of the cost, according to a recent Kaiser Family Foundation survey.

But going after pharmaceutical companies during a pandemic could prove to be risky. “This is probably not the right political moment to be bashing drug companies…when vaccines have been so central to the state’s recovery to Covid,” Kousser at UC San Diego said.

Last year, Newsom signed a bill by Sen. Richard Pan, a Sacramento Democrat, that allows the state to take the first steps in creating state-run generics. The state would partner with manufacturers to make or distribute less expensive generic drugs, including one form of insulin, that would be widely available.

“It’s quite feasible. California is big enough that it can do this. But it’s still going to be hard,” said Geoffrey Joyce, director of health policy at the University of Southern California Schaeffer Center.

It will likely be several years before California makes any of its own generic drugs because many steps must be taken first, such as researching manufacturers and approving funding. An initial report on which drugs the state could target first is due next summer.

“We’ve started some important efforts; they haven’t necessarily yielded their full fruit yet,” said Anthony Wright, executive director of Health Access, a Sacramento-based consumer advocacy group that supported Pan’s bill.

The savings that could be passed on to consumers would likely be modest because the generics industry is already fiercely competitive, Joyce said. In the U.S., “nine out of 10 prescriptions filled are generics, but generics only make about 22% of overall drug spending,” he said.

Rather than trying to lower drug prices, other states have limited what people pay out of pocket. In 2019, Colorado became the first state to cap insulin copays at $100 a month. Fifteen other states have followed suit with some type of co-pay cap on insulin. In California, two current bills aim to prohibit health plans from imposing a deductible on certain prescription drugs — one bill addresses insulin specifically and a second billtargets prescription drugs for some chronic diseases.

Newsom also issued an executive order on his first day in office directing the state to transition all Medi-Cal pharmacy services from a managed care system, in which the state pays health plans an annual fee for each person covered, to fee-for-service, where the state pays for each service provided. That move was expected to result in $612 million in savings for the state in fiscal year 2021-22.

But that transition, first slated for January of this year, has been delayed.

Newsom’s boldest and most controversial promise was to push for government-funded health care for all Californians.

In 2019, Newsom established a Healthy California for All Commission, tasked with figuring out how to get the state closer to universal coverage, including the possibility of a single-payer system. In a single payer system, the government pays for all or most health costs, like in Taiwan and Canada.

Because of the pandemic, the commission postponed several of its meetings last year, pushing back its original timetable. It started meeting again more regularly this year.

Experts say California can get closer to covering everyone by continuing to remove eligibility and affordability barriers. In the most recent budget, for example, Newsom approved opening full-scope Medi-Cal to undocumented Californians 50 and older and agreed to remove what is known as the Medi-Cal asset test, which often forced seniors and people with disabilities to spend down their savings to qualify for free or low-cost coverage. Those two moves alone would allow approximately 250,000 more Californians to get covered.

But some of Newsom’s strongest supporters are holding him to the more ambitious goal of creating one state-funded health plan for everyone.

“We now have a willing federal partner, we have AB 1400, we have this commission, we can act now,” said Stephanie Roberson, government relations director for the California Nurses Association, one of the biggest proponents of single-payer health care.

Assemblymember Ash Kalra, a Democrat from San Jose, pulled AB 1400 or CalCare, which would create the framework for state-paid health care, from consideration earlier this year to iron out financing details.

The bill will be back next year. But the overarching question of how to pay for it has yet to be answered. A single-payer bill that was killed in 2017 carried a $400 billion price tag.

The commission is also exploring other options to pay for the program, including new taxes.

Although some members have expressed concern about the political pushback that comes with new taxes.

“Sometimes in these groups everyone says, ‘oh yeah, no problem it should be easy to get Democrats or progressives to vote for taxes,’ but this is also the land of Prop. 13. If you want to stay an elected official, you’ve got to think carefully about imposing taxes on people,” Pan, who serves on the commission, said at a recent virtual meeting.

While rolling out such a program would be costly at first, University of California researchers found that single-payer systems could save the U.S. money as soon as the first year of operation — with an average drop of 3.5% in total health care spending. Costs would continue to drop over time and the largest savings would come from lower administrative costs and reduced drug costs, according to their review of 22 single-payer strategies.

What California can accomplish isn’t just tied to money and political will. The state also would have to secure waivers to bypass federal rules and get flexibility on how to spend federal dollars. In May, Newsom made the initial ask in a letter to President Joe Biden.

“The big determinant of whether Sacramento will be able to move on single payer is who is in charge in Washington, DC,” Kousser said. “It probably would have taken a Bernie Sanders victory for any state to move forward. Trump would actively block it, but Joe Biden won’t actively encourage it.”

Before the pandemic, Newsom recognized the state was falling short of meeting the needs of its 65 and older population, which is expected to grow by 4 million people by 2030. In mid-2019, he ordered the creation of a blueprint that would set targets to make California more “age friendly.”

The state unveiled its Master Plan for Aging in January with goals around housing affordability, health care, caregiving and economic security. But the work to meet its goals is just beginning. The plan comes with a scorecard that will track the state’s progress over the next 10 years.

Wealthy Activists Reshaping Criminal Justice; Stay Below Radar

Politico

Four wealthy activists intent on reshaping California’s criminal justice system are gearing up for their biggest test yet against police and prosecutor groups.

The Northern California donors, some with fortunes from major Silicon Valley firms, have already spent millions on progressive prosecutors and ballot fights that have helped untether the state from its tough-on-crime past. Now, California’s 2022 attorney general race could be a landmark moment.

The social justice movement has never lacked for energy, and last year’s police killing of George Floyd sparked waves of support for Black Lives Matter and other efforts that have challenged police policies and sentencing requirements as racist. Progressive donors in recent years have strategically targeted prosecutor races in major cities because district attorneys wield power over sentencing and investigations.

In California, social justice advocates are preparing to defend the state’s top prosecutor, Attorney General Rob Bonta, who is closely aligned with the reform movement and one of the nation’s most liberal AGs. The former state legislator was nominated to the post this year by Gov. Gavin Newsom, and Bonta’s election contest next year is expected to be a criminal justice bellwether.

“The last 10 years has been the biggest shift I’ve seen in terms of philanthropic interest in this issue,” said Lenore Anderson, who heads Californians for Safety and Justice. “When you have that shift the door is open … because you’re with the wind of change.”

In California, few causes get very far without a pile of money, given how difficult it is to reach 22 million registered voters across several major media markets.

The four donors — Patty Quillin, Quinn Delaney, Elizabeth Simons and Kaitlyn Krieger — channeled $22 million toward criminal justice ballot measures and allied candidates the previous two years, and their campaign contributions have steadily increased each election cycle. They spent $3.7 million alone to elect George Gascón, who rode the social justice wave that swept over America last summer to unseat incumbent Los Angeles District Attorney Jackie Lacey in November.

Delaney has been involved in criminal justice fights for decades, launching a foundation with her husband Wayne Jordan — a prominent Bay Area real estate developer — after voters passed a 2000 ballot proposition toughening sentencing for youth offenders.

Quillin is a philanthropist and the wife of Netflix CEO Reed Hastings. Simons is a former teacher and the daughter of hedge fund billionaire and philanthropist James Simons. Krieger and her husband, Instagram co-founder Mike Krieger, run a criminal justice nonprofit.

The last decade has brought a remarkable shift in how California punishes crime and oversees law enforcement. Voters and lawmakers have hit reverse on decades of stringent laws that swelled the state’s prisons, backing a raft of bills and ballot initiatives to diminish penalties and increase police accountability. Reformist district attorneys Gascón in Los Angeles and Chesa Boudin in San Francisco have moved away from traditional approaches.

Bonta is facing attorney general opponents who contend he and other reformist prosecutors are undermining public safety, just as homicide and gun violence rates spike in California cities, a trend that mirrors other U.S. population centers.

Quillin, Delaney, Simons and Krieger have already given maximum contributions to Bonta, and they could pour significantly more into an independent committee that can raise unlimited sums. That account is overseen by Anne Irwin, who manages a central hub for their efforts through Smart Justice California. All four donors sit on the group’s board.

“I think the rhetoric of the 2022 attorney general race is going to resemble the dynamic of status quo, lock-em-up-and-throw-away-the key, tough-on-crime versus a new approach to public safety,” Irwin said in an interview.

The major funders have stayed under the radar, and all declined to speak for this story after several interview requests.

They came together in earnest in 2017 with the launch of Smart Justice. Despite victories at the ballot box in 2014 and 2016 that reduced drug and property crime penalties and made it easier for inmates to win parole, Irwin said reformers “were hitting a wall in places we shouldn’t have been hitting a wall” — particularly in the Legislature, where law enforcement unions and groups representing police chiefs and district attorneys wielded significant influence.

“Why were we having these ballot initiative victories, but we can’t get legislators, prosecutors or other elected officials to do the right thing? You don’t have to dig too deep to see the political power dynamics at play,” said Irwin, a former public defender who witnessed the potential of redemption after her father was incarcerated. “Our opponents … had deep pockets and we did not. That showed up and we were losing. It turns out it’s doable with some committed donors.”

They enlisted a top operative, former California Democratic Party Executive Director Shawnda Westly, and sought the counsel of Dana Williamson, a key adviser to then-Gov. Jerry Brown who is now running Bonta’s re-election campaign.

“It’s always more effective when you’re able to pool resources to help elect candidates” and “to champion issues in a coordinated way,” said Williamson, who stressed that she previously advised Smart Justice for free in an unofficial capacity.

In the following years, Smart Justice worked to bend the ears of lawmakers in Sacramento. Simons’ Heising-Simons foundation and Krieger’s Future Justice Fund channeled hundreds of thousands of dollars to Smart Justice, and the women began meeting with individual lawmakers.

“It’s really hard to move beyond the fear-based headlines and to really talk about what happens to everyday people in the courthouse, in the jailhouse, and the police stations, and they are able to help translate that for folks who don’t know,” said state Sen. Sydney Kamlager (D-Los Angeles). “The [district attorneys] and law enforcement come in and say what they want, but they’re also speaking from their own lens.”

Legislators spoke to a growing willingness in Sacramento to defy law enforcement. Part of that is a desire to be on the right side of evolving public opinion. But part of it is a blunt calculation about political risk.

When police unions opposed Assemblymember Reggie Jones-Sawyer (D-Los Angeles), the progressive chair of the Assembly Public Safety Committee, Smart Justice spent $100,000 to successfully defend him. Irwin chaired a committee backing then-state Sen. Holly Mitchell (D-Los Angeles), one of Sacramento’s leading reformers, when Mitchell successfully ran for Los Angeles County supervisor, defeating a fellow Democrat who had drawn the support of police unions.

“It helped me to be able to say to [lawmakers] ‘this is your opportunity to be able to step up and do the right thing and you don’t necessarily have the excuse that you won’t be able to defend yourself after tough votes,’” Mitchell said in an interview. “From my perspective we had moved into the big leagues.”

Law enforcement advocates agreed that power dynamics in Sacramento have markedly shifted, but they argue that progressive reformers and lawmakers have overreached with proposals to ease sentencing and reduce incarceration.

California District Attorneys Association lobbyist Larry Morse pointed to the American Civil Liberties Union sitting atop the list of lobbying expenditures in 2019 as evidence of “the dirty little secret” of pro-reform money “inundating the Legislature.”

“This is far and away the most hostile environment for law enforcement in a generation,” Morse said, adding that in previous decades “things went too far and there were excesses in terms of policies and everything, but that pendulum has swung back the other direction and then some.”

“We frankly get very tired of being characterized as troglodytes because we don’t embrace the scale and scope of what is being pushed as criminal justice reform in this Legislature,” Morse added. “It’s a very lonely task these days to be an advocate for public safety.”

The wealthy donors may have made their most consequential impact in local prosecutor races thus far. Campaigns to elect district attorneys have historically been low-profile affairs in which the support — and money — of law enforcement groups effectively guaranteed victory. But reform advocates have increasingly focused on those contests.

The 2018 cycle was an early test case. While an organization funded by George Soros supplied the most money, pouring millions into four California district attorney races, Quillin, Simons, Krieger and Delaney jointly spent around $360,000 on progressive candidates. Only one prevailed: Contra Costa County District Attorney Diana Becton. Despite that mixed record, Irwin said 2018 laid the groundwork for future campaigns.

“We took the long view: we’re going to inspire folks who are currently in law school and currently in prosecutors’ offices as deputies to think about whether this is a direction you want to go in,” Irwin said. “It was a building block and a moment to test the waters.”

In the next cycle, they plunged in fully, spending millions to help propel Gascón and Boudin to watershed victories. Irwin said Gascón’s decision to challenge Lacey rested in part on knowing the growing network of funders was behind him.

“He knew he wasn’t going to win unless that ecosystem was all-in with him. We knew that too, so it was a little bit of a courting process,” she said. “It wouldn’t have happened without these committed, passionate, resourced folks.”

A backlash followed. Both Gascón and Boudin are facing recall campaigns as Los Angeles experiences a surge in homicides, some property crimes rise in San Francisco and gun violence spikes. Gascón’s own line prosecutors revolted when he told them to stop adding sentencing enhancements that increase prison time, while the California District Attorneys Association backed them in an extraordinary rebuke of a sitting D.A.

Those dynamics will frame Bonta’s attorney general re-election push. Bonta was a criminal justice reform stalwart in Sacramento and progressives’ favored attorney general pick. He started his tenure by vowing to repair what he calls a broken relationship between law enforcement and the communities they police, and he has already clashed with the California District Attorneys Association.

Bonta’s opponents include Sacramento District Attorney Anne Marie Schubert, who has sought to link Bonta to what she calls the chaos and lawlessness encouraged by Gascón. Schubert left the Republican Party in 2018 and registered as a decline-to-state voter. She helped solve and then prosecuted the Golden State Killer case, a major breakthrough after decades of going cold.

Law enforcement interests have already lined up behind Schubert, who in 2018 prevailed over reformer-backed challenger Noah Phillips. “That influx of money into Sacramento was not successful,” Schubert said in an interview.

“I am proud to be the chief law enforcement officer of Sacramento, I would be proud to be the chief law enforcement officer of the state, and I would be proud to be supported by law enforcement. I’m not going to shy away from that,” Schubert said. “There’s been, since 2016, a lot of influx of money from what I would call supporters of the types of reckless policies” she is running against.

The 2022 election will set those competing visions against each other. Voters will be warned that reforms have gone too far and imperiled public safety. They will also hear that entrenched law enforcement interests are trying to unravel the state’s badly needed progress. The women who have worked to achieve those changes stand ready to defend them.

“I am forever grateful,” Mitchell said, “that they are choosing to use their superpowers for good.”