For Clients & Friends of The Gualco Group, Inc.

IN THIS ISSUE – California’s New Economic Rating: “From Sizzling to Ho-Hum”

POLITICS

- Legislature to Mark A Decade of Democrat Supermajority…And A Bad Week for Statewide Officers

- California Republicans Confront “Bleak Reality”

- Bipartisan Skeptics Greet Newsom’s $12 Billion for Homeless

FORCES OF NATURE

- “City of Dingbats” Solved A Housing Crisis

- Golden State’s Economy Recovery Slows From “Sizzling to Ho-Hum”

- California Has 30% of Nation’s Unemployment Claims; 11.7% of Work Force

- If “Fast And Furious” Drought Continues, Statewide Water Restrictions Loom

- Forest-Thinning – Recently Controversial – Saved Lake Tahoe & Sequoias

- Public Utilities Commission Chief Abruptly Resigns

Capital News & Notes (CN&N) harvests California policy, legislative and regulatory insights from dozens of media and official sources for the past week. Please feel free to forward this unique service.

READ ALL ABOUT IT!

FOR THE WEEK ENDING OCT. 1, 2021

Legislature to Mark A Decade of Democrat Supermajority…And A Bad Week for Statewide Officers

CalMatters

When the Legislature resumes session in January, it will mark the 10th year of the election in which they first won a supermajority of seats in both houses of the Legislature.

In the decade that followed, they’ve largely held on to that power. But the ability to muster a two-thirds vote in the Senate and Assembly has never quite lived up to its promise or the warning from Republicans — tax increase votes have been rare, gubernatorial vetoes have not been overridden, and sweeping constitutional amendments have not been placed on the ballot.

Instead, the state Capitol’s never-ending battles between business and labor groups have mostly moved from a two-party fight to one inside Democratic ranks. Much of that has been in the 80-member Assembly, where 18 Democrats voted on the side of positions taken by the California Chamber of Commerce most of the time in 2020 and an additional seven were almost split on backing the business group’s views.

The biggest change has been in elections, and we’ll see more of this next year. In 2018, two statewide offices featured Democrat versus Democrat races in the general election.

In the coming cycle, that could happen again for the post of state insurance commissioner. On Monday, five-term Assemblyman Marc Levine (D-Greenbrae) announced he would challenge Commissioner Ricardo Lara, saying that “too many distractions” were keeping his fellow Democrat from doing the job and subtly hinting at criticisms of Lara two years ago for accepting campaign contributions from insurance industry executives.

Lara quickly responded with a dizzying list of Democratic endorsements featuring Newsom and every other statewide elected official as well as more than five dozen members of the Legislature.

It hasn’t been a good week for California’s statewide elected officials. On Tuesday, the Sacramento Bee reported that Treasurer Fiona Ma — who is facing a sexual harassment lawsuit from a former employee — frequently shared hotel rooms with staff, a practice she said saved the state money.

On Wednesday, Politico reported that Superintendent of Public Instruction Tony Thurmond allegedly created such a hostile and toxic work environment that nearly two dozen top officials have fled the agency since 2019, when he took over as California’s schools chief. It’s the latest story to raise questions about how Thurmond is wielding the power of his office — in March, CalMatters’ Laurel Rosenhall reported that Thurmond had remained largely behind the scenes during the pandemic, despite the disruption to 6 million students’ education.

A few examples illustrating the level of turnover at the California Department of Education since Thurmond took over:

- Nine officials have been assigned to help oversee State Special Schools, which leads education for deaf and blind students.

- Thurmond has had three directors of communications and three chief deputies of public instruction — the department’s No. 2 officer — in less than three years.

In a sign that Thurmond is taking the allegations seriously ahead of next year’s election, he retained Nathan Click, a longtime Newsom spokesman, as a crisis communications consultant. And a Wednesday press conference at which Thurmond was scheduled to unveil “a new effort to improve African American student achievement in the state” was cancelled, though the superintendent did visit a wildfire-affected school to pass out face masks and gift cards.

California Republicans Convene to Confront “Bleak Reality”

Politico’s California Playbook

It took a decade of electoral defeats and the humiliation of this month’s failed gubernatorial recall. But as the California Republican Party gathered in San Diego over the weekend for its biannual convention, the bleak reality finally sunk in.

For the foreseeable future, as even party stalwarts here concluded, Republicans will likely not win top-of-the-ticket statewide races — or even compete seriously in them.

With the convention unfolding in half-empty meeting rooms at a waterfront hotel, there was no feting of Larry Elder, the conservative radio show host who enthralled the party’s rank-and-file in the recall — though that was nowhere near enough to unseat an incumbent Democratic governor.

Nor was Kevin Faulconer, once widely considered the future of the state party, on the convention program. The former San Diego mayor, who did even worse than Elder in the recall election, took private meetings on the patio of a restaurant several blocks from the convention hotel, avoiding any confrontation with party activists who disdain his moderate politics. (Faulconer said in an interview that he planned to meet privately with delegates at the convention site, despite not speaking there, and “of course” felt welcome at the convention).

For years, Republicans in California have run candidates for marquee statewide races, lost and then regrouped, certain that the next time they might have a chance. But following their drubbing in the recall , party organizers are resigning themselves to the math. In a state where Democrats now outnumber Republicans nearly two-to-one, Republicans will compete in local races in parts of the state where they remain competitive, including in congressional districts in Orange County and suburban Los Angeles — where the outcome of several House races could determine the balance of power in Washington next year. But hardly anyone sees the party competing seriously statewide.

“We’re down to, what, 23 or 24 percent [registration]?” said Randall Jordan, chair of the Tea Party California Caucus. “We don’t have a lot of influence in the state of California.”

There’s no obvious fix for the party on the horizon. While Republicans in Democratic-leaning states like Massachusetts, New Hampshire and Maryland found success in past election cycles recruiting relatively moderate members of their party to run for statewide office, the recall in California laid bare how much more difficult that calculation may be in the post-Donald Trump era. In the recall, the party’s activist base would not tolerate Faulconer, a centrist, and deprived him of support. The base’s chosen, more Trump-like candidate, Elder, won over Republicans but could not seriously compete for the Democratic and independent votes necessary to win.

The result is that the Republican Party in the nation’s most populous state is poised to focus not on statewide races, but on the red and purple pockets of California where it holds congressional districts or could flip them. It’s now less a statewide operation than a regional one. “Listen, we play in the fights that we can win,” said Jessica Millan Patterson, the chair of the state party.

On Sunday, she told delegates that in 2022, the focus of the state GOP will be on helping Republicans retake the House — “on retiring Nancy Pelosi and replacing her as speaker of the House with a Republican from California, Kevin McCarthy.”

Conspicuously absent from the party confab was Elder, the Republican who led the recall replacement field. (He was on the opposite coast, tweeting that he was “recovering from the campaign in Key West, Florida.”) As Carla reports, Elder’s meteoric ascent energized conservative voters even as his views alienated others, sharpening enduring questions about the CAGOP’s ability to appeal to a statewide majority.

Bipartisan Skeptics Greet Newsom’s $12 Billion for Homeless

Politico’s California Playbook

Gov. Gavin Newsom was signing bills and talking up the homelessness issue Wednesday in Los Angeles.

Which is why Fran Quittel was fuming. And why Quittel — a lifelong Democrat who voted against recalling the governor — and the Republicans who pushed for Newsom’s ouster may find themselves on common ground these days.

Quittel is the vice chair of the budget advisory committee in Emeryville, a Bay Area community that has, despite its new apartment towers and busy shopping centers, become Ground Zero for some of the most visible and intractable homeless encampments in Northern California.

Those camps, which stretch along I-80 from Oakland to Berkeley, have mushroomed in recent years and now spill onto nearby off ramps. The crumpled bikes, furniture, tires and shopping carts along highway embankments seriously endanger drivers on a regular basis, she told POLITICO.

“What I’m talking about [is] rolling objects on a roadway and all kinds of flying debris,’’ said Quittel, who said she’s contacted Caltrans and government officials more than 75 times about these hazards. Nothing has changed, she said.

“There is not a landlord in the state of California who could get away with these kinds of conditions,’’ including having people “using buckets for their excrement and urine” in public. “This is California, can you believe it?”

Quittel said she came very, very close to voting for the recall after watching the governor turn up in the weeks before the recall, in jeans and t-shirt, to help clean up these very same on ramps while photographers snapped away. In the end, she said, control of the U.S. Senate — recall frontrunner Larry Elder swore to appoint a Republican to Sen. Dianne Feinstein’s seat, should the 88-year-old step down early — dissuaded her from that.

The governor acknowledged the depth of the public anger over the state’s chronic housing troubles. “We have a unique responsibility … because nothing like the homeless crisis exists anywhere else in the United States like it exists and persists here in the state of California,’’ he said. “There is no other issue that raises the anger and ire and frustration — and just general concern — than homelessness,’’ he said. “We are here to get back on the right side of history.”

Newsom’s event featured a parade of legislators, who praised the governor for not “kicking the can down the road’’ as they unveiled a new interagency council on homelessness.

Already, the governor said, his team “has identified 100 high-profile encampments around California, and we’ve actually attached timelines and strategies to begin to clean them up permanently.” But he also expressed deep frustration, when he added: “There is a specific encampment in Northern California that we were trying to clean up recently, in and around the Berkeley area — and the judge just put a six-month pause on our ability to help those folks.” (Not that his participation in an encampment clean-up last month went over particularly well with homeless advocates.)

Still, Quittel said it will take more than a new government entity and some photo ops and press conferences to convince her that the state under Newsom will ever make progress. It will take compassion for the unhoused, she said, but also real change — right on the off ramps she passes every day.

“He’s living in a fog if he thinks giving $12 billion’’ — the amount set aside in his 2021 fiscal budget — “to the same ineffective people is going to solve the problem,’’ she said. “That will be a waste of taxpayer money.”

BOTTOM LINE: Newsom may be safe from the recall, free to focus on his 2022 reelection campaign, but this is one issue that isn’t going away. He’s still got some real convincing to do — even within his own party.

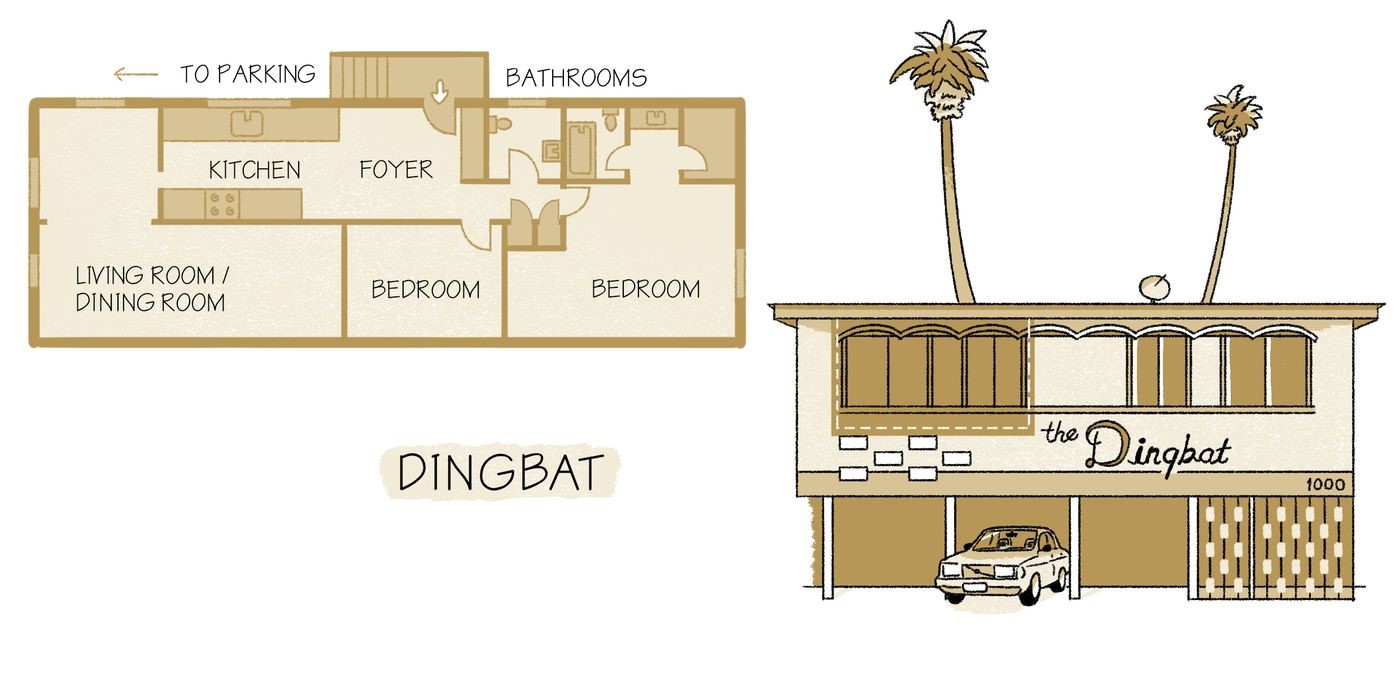

Los Angeles Became the City of Dingbats…And Solved A Housing Crisis

CityLab / Bloomberg

Faced with a housing shortage, Los Angeles once had a solution:

Colorful carport-equipped apartment buildings offered affordable — and sometimes stylish — digs for generations of L.A. dreamers.

From the San Fernando Valley to Culver City to La Cienega Heights, developers in the 1950s and ’60s tore down thousands of older buildings and filled in virtually every square foot with aggressively economical two- or three-story apartment complexes — known locally as dingbats.

Subdivided into as many units as the lots could accommodate — usually between 6 and 12 — most of these stucco boxes left little room outdoors, except for an exposed carport slung beneath the second floor. This new format for affordable multifamily living became nearly as ubiquitous as the single-family tract housing that iconified the much-mythologized Southern California suburban lifestyle.

British architecture critic Reyner Banham popularized the term, which both captures the buildings’ somewhat addled appearance and riffs on the ornamental glyphs used by typesetters.

But dingbats did provide an essential resource for a growing city. Los Angeles County added more than three million residents between 1940 and 1960, thanks to job booms in manufacturing and aerospace, educational opportunities for returning GIs, and the lure of year-round sunshine.

Construction raced to keep up, with more than 700,000 housing units built countywide in the 1950s. New highways allowed much of this growth to sprawl into the suburbs: Vast numbers of cookie-cutter homes replaced citrus groves and ranchlands, sold as one’s own little slice of Elysian movieland, complete with driveway and pool.

Dingbats were a multifamily answer to that single-family template: Often built by small developers and mom-and-pop property owners who lived in the back, they were designed to house single people, young couples, and other upwardly mobile new residents, of which there were many.

They also uniquely captured the mix of sun-drenched fantasy and hard-edged reality that remains integral to the city’s essence — after all, no place can stay a paradise forever when you actually live there.

In his path-breaking 1971 appraisal of Southland urbanism, Los Angeles: The Architecture of Four Ecologies, Banham called them “the true symptom of Los Angeles’ urban Id, trying to cope with the unprecedented appearance of residential densities too high to be subsumed within the illusions of homestead living.” Now, as 21st-century problems call for revising that suburban dream, the dingbat holds timely lessons within its stucco walls.

The first of those lessons might be that aesthetics aren’t everything. Invariably rectangular, flat-edged, and built of the cheapest materials, dingbats are unapologetically utilitarian.

Yet they are anything but blank-faced. Many prominently display a single ornament, such as a starburst or boomerang, or feature decorative trimmings with a Tiki, French Chateau, or Space Age aesthetic.

Pastel paint jobs are common, as are aspirational building names splayed on giant signage legible from passing cars. Such affectations could be seen as mirroring the city’s reputation — fair or not — as a land of artifice.

“They’re stylistically diverse with exotic names, but they present as what they aren’t,” said Thurman Grant, co-editor of Dingbat 2.0: The Iconic Los Angeles Apartment as Projection of a Metropolis. “It is literally a dumb box with as many units packed in as possible, with a slapped-on facade.”

Many Angelenos considered these new constructions a visual blight, and still do. Before Banham, the dingbat moniker was already in use as a pejorative, including in reference to low-quality, ugly construction. California historian Leonard Pitt once wrote that “the dingbat typifies Los Angeles apartment building architecture at its worst.”

Yet like a species that adapts to its environment, dingbats were a response to the demands of their moment. City zoning codes required only one vehicle space per housing unit of more than three habitable rooms, which allowed for the dingbat’s relatively modest parking footprint at grade level (this would change after increased parking minimums and other development restrictions made dingbats less economical to build, as the architectural historian Steven Treffers has noted). In the age of the automobile, they gave lower-income households a foothold in the California suburb-scape, with some of the same cheery trimmings as single-family homes but at a price many could afford.

MORE:

Golden State’s Economy Recovery Slows From “Sizzling to Ho-Hum”

LA Times

Remember when the economic recovery in California and the nation was going to seem like the Roaring ‘20s? That was what UCLA forecasters predicted nine months ago.

Remember when it was likely to be “euphoric”? So they said six months ago.

Or when it was expected to be “boom time for the U.S. economy”? That was three months ago.

But the Delta variant of the coronavirus has upended the calculations of forecasters — not just at UCLA Anderson’s widely cited group, but among academic, government and corporate economists nationwide.

The outlook has gone from “sizzling to ho-hum,” the UCLA quarterly forecast, released Wednesday, reported.

“Back in the spring, the economic optimism was palpable,” senior economist Leo Feler wrote. “The U.S. was vaccinating an average of 2 to 3 million people per day. The economy was reopening. Hiring was accelerating. It looked like COVID was finally behind us.”

But with entrenched vaccine resistance and rising deaths in many states, consumers are hesitant to go out and spend on entertainment and restaurants, workers are retiring rather than risk infection on the job, business and international travel are dormant and global supply chains are going haywire as the virus closes factories abroad, Feler said.

“What could have been a couple of years of blockbuster economic growth look instead to become years of good, solid, but not spectacular growth.”

UCLA predicts gross domestic product will grow this year at 5.6%, down from the 7.1% rate forecast in June. It expects the economy to expand by 4.1% next year, down from the 5% anticipated earlier.

As consumption and investment shift into the future, 2023 growth could be3.1%, up from the previously forecast 2.2%.

UCLA’s forecast for this year is slightly less optimistic than that of the Federal Reserve, which projects GDP growth at 5.9%, down from its June forecast of 7%. The Fed predicts 3.8% growth next year.

California began recovering later than some other states because of its stricter public health measures, but those interventions will mean the state rebounds faster than the nation over the next three years, UCLA economists Jerry Nickelsburg and Leila Bengali suggest.

California’s unemployment rate has been stubbornly high, and its 7.5% August rate was the second highest state rate in the nation, behind only Nevada. While California’s rate is expected to drop, it will take awhile before it matches the national rate, which was 5.2% in August.

California’s unemployment rate, traditionally higher than the nation’s partly because of the state’s reliance on tourism, leisure and hospitality, is expected to average 7.6% this year, 5.6% next year and 4.4% in 2023.

In 2019, before the coronavirus hit, Golden State joblessness had dropped to 4.2%.

For the U.S., the forecasters predict unemployment will fall from 5.6% this year to 4.4% next year and 3.7% in 2023, the same as in 2019.

“Delta has spooked consumers,” Nickelsburg wrote. “News reports on breakthrough [infections] and the large number of Californians not vaccinated will likely push a full recovery into the latter part of 2022.”

Other forecasters are less optimistic. “I don’t expect a full California jobs recovery until late 2023 or even 2024,” said Scott Anderson, chief economist at the Bank of the West in San Francisco. “California’s economic performance won’t be quite as strong as they project with their rosy assumptions around better health outcomes.”

As of Sunday, the Golden State had the lowest weekly coronavirus case rate of any state: 83 cases for every 100,000 residents. That compares with 271 cases in Texas and 248 cases in Florida — states with loose regulations.

A boost to the state’s economy is that the virus has led to more remote work — a factor that benefits its large technology and professional sectors.

The job market will depend on the uncertain course of the pandemic, the forecasters wrote, but they expect California’s employment to rise by 3.5% this year, 3.9% next year and 2.7% in 2023.

That contrasts with projected U.S. employment growth of 3.1%, 3.2% and 2.1% over the same three years.

As for complaints about labor shortages, U.S. businesses may be posting 11 million job openings and 8 million people may be unemployed nationwide, Feler said, but “sectors demanding work are different from sectors where people used to work. California may have openings in tech and engineering, but how does that help someone who worked in leisure and hospitality?”

Moreover, he said, “Being a restaurant server before wasn’t a risky job. Now it is. And it is hard to go back to the labor force when your kid might be sent home from school and quarantined for 10 days. You need a job that’s very flexible.”

One bright spot in California is logistics. Asian imports are flooding through the giant ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach and spurring construction of distribution centers across the Inland Empire, buoyed by booming pandemic-related demand for such things as home gym equipment, electronics and furniture, as consumers spend on goods rather than travel, dining and movie tickets.

Golden State transportation, warehousing and utility jobs are forecast to grow at the highest rate of any sector this year: 5.4%, slightly above leisure and hospitality’s 5.3%.

Meanwhile, shipping prices have skyrocketed, dozens of vessels are anchored off Southern California because of logistics bottlenecks, and many imported goods, including windows, semiconductors and automobiles, are in short supply — factors that contribute to inflation.

https://www.anderson.ucla.edu/about/centers/ucla-anderson-forecast

California Has 30% of Nation’s Unemployment Claims; 11.7% of Work Force

CalMatters

California now accounts for nearly 30% of the nation’s new unemployment claims despite making up just 11.7% of the labor force, according to federal data released Thursday. Nearly 87,000 Californians filed new jobless claims for the week ending Sept. 25 — an uptick of nearly 18,000 from the week before, and the state’s highest total in six months. The dismaying numbers come about three weeks after the federal government cut off benefits for 2.2 million of the 3 million Californians receiving some form of unemployment insurance, suggesting that expanded aid was not the main reason keeping employees from returning to work, as some experts had argued. The data also bolsters recent forecasts that California’s economy will recover more slowly than expected — as indicated by an unemployment rate that has barely budged in months.

If “Fast And Furious” Drought Continues, Statewide Water Restrictions Loom

Associated Press

California’s reservoirs are so dry from a historic drought that regulators warned Thursday it’s possible the state’s water agencies won’t get anything from them next year, a frightening possibility that could force mandatory restrictions for residents.

California has a system of giant lakes called reservoirs that store water during the state’s rainy and snowy winter months. Most of the water comes from snow that melts in the Sierra Nevada mountains and fills rivers and streams in the spring.

Regulators then release the water during the dry summer months for drinking, farming and environmental purposes, including keeping streams cold enough for endangered species of salmon to spawn.

This year, unusually hot, dry conditions caused nearly 80% of that water to either evaporate or be absorbed into the parched soil — part of a larger drought that has emptied reservoirs and led to cuts for farmers across the western United States. It caught state officials by surprise as California now enters the rainy season with reservoirs at their lowest level ever.

“Nothing in our historic record suggested the possibility of essentially that snow disappearing into the soils and up into the atmosphere at the level that it did,” California Natural Resources Secretary Wade Crowfoot said. “These climate changes are coming fast and furious.”

California’s State Water Project — a complex system of dams, canals and reservoirs — helps provide drinking water to about 27 million people in the state. In December, state officials will announce how much water each district can expect to get next year.

Thursday, Department of Water Resources Director Karla Nemeth said the agency is preparing for what would be its first ever 0% allocation because of extraordinarily dry conditions.

“It’s a done deal, we’re sure that we will get a zero,” said Demetri Polyzos, manager of resource planning for the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California that provides water for about 19 million people. “These are uncharted territories, what we are seeing.”

The December announcement acts as an initial estimate. It could change later if things improve. That’s why this winter is so important. It’s impossible to predict with accuracy how much rain and snow California will get this winter. But if it’s anything like the last two winters, there will be even bigger problems.

California’s “water year” runs from Oct. 1 through Sept. 30. The 2021 year ends Thursday, and it was the second driest year on record, according to the Department of Water Resources. California had its warmest ever statewide monthly average temperatures in October, June and July, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s National Centers for Environmental Information.

The 2021 water year began with reservoirs at 93% capacity. But California won’t have that cushion this year. The state’s reservoirs are at 60% of their historic average, state officials said.

The State Water Project provides about 30% of the Metropolitan Water District’s supplies, with the Colorado River supplying about 25%. The district also has some local supplies, including water it has in storage.

Last month, the agency declared a “water supply alert” and called for voluntary conservation. They’re offering rebates for things like more efficient shower heads and appliances and replacing grass lawns.

Despite the severity of the drought, Gov. Gavin Newsom has not declared a statewide emergency. Instead, he has declared emergencies in 50 of the state’s 58 counties, an approach his administration says is driven by lessons learned from the most recent drought when the state imposed restrictions statewide.

“(Water agencies) have explained to us that one size fits all mandates from Sacramento sometimes have unintended consequences,” Crowfoot said.

Still, California’s water supplies are in poor condition heading into the rainy season. In July, Newsom asked everyone to voluntarily reduce their water use by 15%. But in the first three weeks after that request, Californians reduced their water usage by just 1.8%, state officials said.

In a call with reporters on Thursday, Crowfoot said mandatory water restrictions “need to be on the table.” But he indicated those restrictions likely wouldn’t come until state officials have a better idea of how much water the state will get this winter.

“This winter will be determinative in terms of what additional actions we need to take on conservation,” Crowfoot said. “We’ll be watching.”

Forest-Thinning – Recently Controversial – Saved Lake Tahoe & Sequoias

Wall Street Journal excerpt

MEYERS, Calif.—As the Caldor Fire approached this Lake Tahoe town last month, the flames burned 150 feet high and embers rained down from the sky. But not a single house burned.

That is largely because fire crews had thinned the forests that surround the town, chopping down small trees, sawing low-hanging limbs and clearing the forest floor of combustible debris. With much less fuel to burn, the blaze was smaller and moved slower, making it easier to control.

“When it hit this thinning, the flames dropped down to 15 feet,” said Milan Yeates, a forestry supervisor for the California Tahoe Conservancy, a state agency.

Similar thinning protected a grove of giant trees in Sequoia National Park, including the General Sherman, the largest tree in the world by mass, when the KNP Complex of wildfires threatened it earlier this month.

Firefighters and land-management agencies across the American West have recognized for decades that one of the most effective tools to reduce wildfire risk is to thin forests, whether by removing dead trees and brush in accessible areas or reducing the most flammable elements with controlled burns in remote ones. Between 1999 and 2019, the use of intentionally set fires by state and federal agencies tripled to six million acres a year, according to the National Interagency Fire Center.

But that isn’t enough to keep up with the rising wildfire risk caused by drought, climate change and homes built too close to wild lands, according to researchers.

“We need two to five times more fire and thinning,” said Mark Finney, a research forester for the U.S. Forest Service based in Missoula, Mont. “This needs to be a consistent, long-term program.”

One factor hindering forest-thinning is the wildfires themselves, which have grown in both size and intensity in recent years, leaving firefighters with less time for prevention.

Other obstacles to thinning include regulatory delays caused by the Covid-19 pandemic and a lengthening fire season, which is shortening the period during which prescribed burns can be done safely.

Around Lake Tahoe, piles of thinned wood remain scattered around the forest awaiting disposal by burning that has been delayed by dry conditions the past two winters, said Gwen Sanchez, acting supervisor for the Forest Service’s Lake Tahoe Basin Management Unit.

Prescribed fire was widely used in the Western forests by Native Americans, in part to keep insects out of acorns they ate, said Susie Kocher, forestry and natural resources adviser for the University of California Cooperative Extension.

For most of the 20th century, though, the policy of land authorities in the West was put out wildfires as quickly as possible—which made forests increasingly flammable. Prescribed burns were reintroduced to Sequoia National Park in the 1960s and to other regions by the 1990s.

Increasingly ambitious forest-thinning targets have been set recently, but the government has struggled to reach them. California Gov. Gavin Newsom last year signed an agreement with the U.S. Forest Service that called for joint thinning of one million acres a year. To help achieve that, Cal Fire plans to thin 100,000 acres annually by 2025. But as of last year, it was operating with a goal of half that area, an agency spokeswoman said.

Public Utilities Commission Chief Abruptly Resigns

Sacramento Bee

Marybel Batjer, who steered the California Public Utilities Commission through a brief but tumultuous era of wildfires, bankruptcy and blackouts, announced her resignation Tuesday.

Batjer, in a letter to the commission’s staff, said she will end her tenure at the end of December, just two years after she was appointed by Gov. Gavin Newsom. Her term wasn’t due to expire until 2027.

A veteran of decades in state government, Batjer leaves as the state wrestles with instability in its electrical system and investigations into its largest utility, PG&E Corp., and the role it may have played in recent wildfires.

A former government operations secretary, Batjer took over the top job at the commission in August 2019, as Newsom and other state officials were wrestling with PG&E’s bankruptcy. PG&E was driven into Chapter 11 months earlier by a series of catastrophic wildfires, including the 2018 Camp Fire, which left the company owing billions in liabilities.

Amid complaints that the commission hadn’t done enough to police the company, Newsom, Batjer and others brokered an agreement that allowed PG&E to successfully exit bankruptcy in 2020, with an overhauled leadership and operational structure.

The deal included a six-step regulatory model that enables the Public Utilities Commission to step up its oversight of PG&E if the company fails to meet certain safety standards. If the company reaches the sixth step, it could be subject to a state takeover.

The commission voted in April to take the first of the six steps after concluding PG&E had fallen behind on trimming trees and removing other hazards that could spark a wildfire. Since then, the company has come under investigation by Cal Fire in connection with the Dixie Fire, the second-largest in California history. Officials believe the fire was started when a tree came into contact with PG&E power equipment.

On Batjer’s watch, the commission has also had to grapple with troubles on the state’s power grid. In August 2020, just about a year after she took over at the PUC, the state was plunged into two nights of rolling blackouts during a 110-degree heat wave. Although the grid is run by a different entity, the Independent System Operator, Batjer’s agency took some of the blame for the power shortage. A lengthy postmortem, co-written by the system operator, Public Utilities Commission and Energy Commission, blamed the blackouts on poor planning.

In the months since, the PUC has worked on various strategies for bolstering reliability of the grid, including a recently-announced cash-for-conservation program that pays big industrial customers for turning off their electricity during crunch periods. No blackouts have occurred this year despite some close calls.

The utilities commission has also dealt with internal strife during Batjer’s tenure. In September 2020 the commission fired its executive director, Alice Stebbins, saying she had hired or promoted unqualified employees and demonstrated insubordination when her actions were investigated. She initiated legal action against the commission, saying she was fired for being a whistleblower.

In her resignation letter, Batjer said, “This was a difficult decision, as I am so proud of the work we have done together in the face of a changing climate and global pandemic.” She added: “I have had the privilege of serving four California governors and have given my all to public service for many decades. I am now ready for a new challenge and adventure.”

https://www.sacbee.com/news/california/article254590317.html?#storylink=cpy